Review

A fantastic book on the developing science of Evo Devo. Carroll manages to correct the course of thought away from the incorrect assumption that evolution is primarily driven by the accumulation of totally random, proteinaceous mutations, amongst which a handful are beneficial. One change in one protein is infrequently the cause of such fervent radiation and speciation. Instead, the random accumulation of mutations of so called “switches” in the non-coding DNA of an organism provide upstream, much broader-stroked changes to the development and functioning of an organism. The focus of the book seems to teeter toward the start of “Act II”, as well as a deal of exhaustive repetition in the conclusion (though I suppose the point of a conclusion is to be wholly conclusive). The continued appearance of certain “superstar” Hox genes (here’s looking at you, Distal-less) was a pleasure to read – showing up in at-first unexpected locations across taxa. In summary, this is a fantastic introductory read, that eventually blossoms out to encompass multiple fields of ecology, anthropology and palaeontology in much narrower, academic scope – however the early chapters acts as sufficient preparation to soften the blow of certain genetic formulae and more complex Hox gene diagrams that follow. Thoroughly enjoyable, thoroughly recommended.

Discussion

This book is now a firm favourite of mine and, even having studied Evo Devo, I feel like I actually get the appeal of the subject a lot more after reading. One of the best thought exercises the book poses is that of the “evolution” of eating utensils in early humans. In summary, we know that the knife was the original multipurpose eating tool – prehistoric humans would carve and stab meat with the same knife, using it to carry the food to their mouth. A little while later, humans realised if they used two knives, one could be used for carving, and another for holding the meat in place during carving and subsequent lifting to the mouth. This secondary knife then “evolved” separately to be much better at the holding and the lifting, and less so at the cutting, which the primary knife already had under control: boom, fork!

This is the part that blew me away, as I had always struggled with understanding the specialisation of different proteins, limbs or features of an organism after duplication events – “why not keep them multipurpose?” I had (perhaps naïvely) thought. However, multipurposeness (multipurposity?) is not the desirable endpoint it seems – it’s actually the exact opposite: a starting point from which to diverge and diversify. Picture an organism that has two desires: it wants to be able to cut through things, but also wants to be able to swim very well. The old me would have thought “well surely the best choice is a limb that succeeds at both tasks!”, but this limb is perhaps not at all possible. To cut efficiently, you need a thin, aero/hydrodynamic profile with a very sharp leading edge. To swim successfully, you need a wide, paddle like shape with lots of surface area perpendicular to the direction of movement. These limbs are the antitheses of one-another – there is no neutral ground that succeeds at both tasks, it can only aim to fail at both.

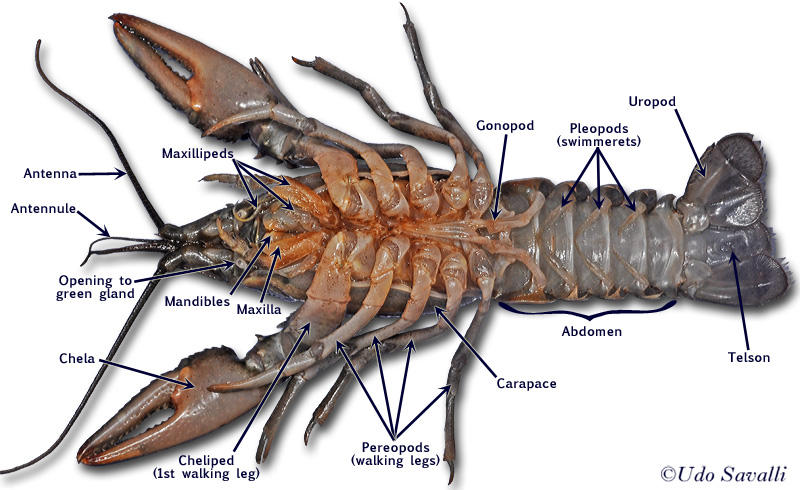

So what do you do as this organism? Well, picture you have this one limb type already – maybe you’re an invertebrate with a few segments that each have a pair of limbs, and maybe they’re pretty good at cutting! Great stuff. However, theyre quite thin to achieve this task and, as a result, you’re having trouble swimming. Through the generations, duplications and alterations in your Hox genes cause your segment number to increase – now you have a few more limbs to play around with. However, these are still the cutty-limbs, and you don’t really need any more of those – you’re all set vis-a-vis cutting. Therefore, this duplication event gives you a very small leg-up (hee hee) against your competition. However, after a few more rounds of reproduction, you undergo a strange mutation so they aren’t great at cutting – however, this doesn’t place you at a disadvantage, as you’ve got cutting limbs to spare. Notice how, now, you’ve got *options*, something you didn’t have much of before, as any mutation to your vital cutty-parts would be negative BEFORE they get positive.

This is a beautiful part of Evo Devo theory I love called the Wright’s Fitness Landscape. To understand this, picture the gene-space as a 2D or 3D environment, where the x (and z) axes represent arbitrary genetic “change” and the y-axis represents fitness of the organism. There are hills of high fitness, separated by valleys of low fitness, which it would kill to pass through (hence why species tend not to vary too far from the “genetic mean”).

In terms of the WFL, this segment duplication event gives you a bridge between peaks, raising the Valley of Death into a Plateau of Potential. Radiate out; explore your options and diversify the extra limbs with a limited no-detriment buffer.

Perhaps this mutation in your “spare” limbs widens them, lowering the hydrodynamic profile. They seem bad at cutting, but you notice not THAT bad at swimming! This is really good as far as you and your lineage are concerned – a few more rounds of reproduction and mutation accumulation and you’ll have some beautiful new swimmerets! Congratulations, you’ve just specialised your limbs!

Why don’t you take a selfie to celebrate your achievements?

Oh, you saucy devil.